Epic seems to feel like it gets enough value from the fee it pays console makers, but not from Apple. Never mind that Apple builds and supports the tools required to create iOS apps. Never mind that Apple invests in hardware that is capable of running apps and games built on Epic’s Unreal Engine.

Of course, Epic also takes a cut on its own app store with in its games. Epic might argue that it only takes 12 or 15 percent, but the argument hasn’t been that Apple takes too large a cut, but that Apple takes a cut at all. Tim Sweeney says he’s against middlemen, but seems to be just fine with them, as long as it’s him.

Epic might have a moral point to make in terms of whether Apple should have as much control as it does, but it certainly went about it in a way that cost it the moral high ground. It doesn’t matter how much you dislike something, or how many people agree with you, you still don’t get to simply decide you’re not going to abide by the terms you agreed to and not expect to get booted.

Of course, that was exactly what Epic was hoping for.

The problem is, Epic isn’t acting in good faith. There’s no question that Epic made this move intentionally and with the knowledge that it was breaking the rules. It also was fully aware of the consequences of such an action. It’s hard to give it credit for starting a moral revolution against Apple when its motivation isn’t pure and it’s tactics aren’t moral.

It’s pretty clear that even if you think Apple has far too much control and is taking far too large a cut, Epic is wrong. You can even think that the point Epic is trying to make is correct, but everything about the way it went about it is wrong. This isn’t civil disobedience, it’s a coup attempt.

No Soliciting

Apple isn’t going to allow Epic, or anyone else, to add its own app store to the iPhone. There are plenty of reasons for this, and money is only one of them. While I actually think there are even better reasons, let’s assume for a moment that money is the only reason. Before you think that’s a selfish reason, consider that no business anywhere is okay with a vendor standing inside their front door attempting to sell on its own the products it also offers on the shelf.

Or, would Walmart ever allow Amazon to set up a tent sale in its parking lot? Of course not. And we’d never criticize Walmart on the grounds that its stifling competition. The opposite is true—it’s competing, which means that it is making decisions, by definition, to advance its own business against all the others.

Sure, sometimes businesses enter into partnerships when they feel it would be mutually beneficial. Again, those are decisions made to advance individual businesses. The fact that one business is willing to make a specific decision isn’t a reason that every business should be required to do the same.

In this case, Epic’s goal is clear—it wants to cut Apple out of a space it would rather occupy itself. That’s is certainly Epic’s prerogative, but it shouldn’t be surprised Apple isn’t having any of it.

Microsoft Is Also Wrong

While much of the focus is on the Epic battle, mostly because it is obviously the most public, the irony is that there are businesses with a much stronger case to make against Apple’s rules. Take Microsoft, for example.

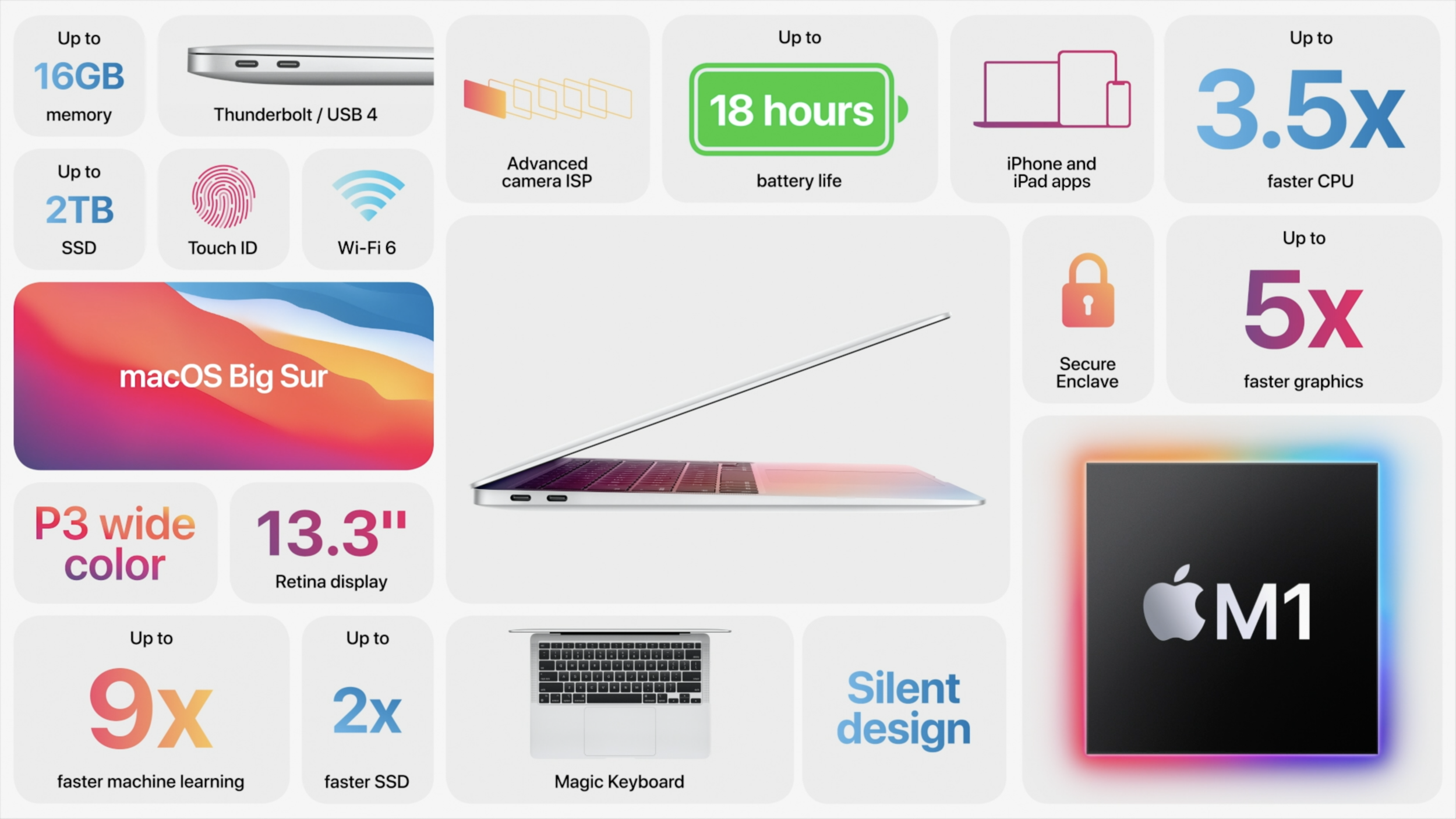

Microsoft wants to bring its streaming game service to iOS, previously known as xCloud, which would allow iPhone users to play a catalog of major games like HALO via a monthly subscription fee. I’m not going to get to far into the technical aspects of how a gaming service that simply streams the games from a central server works, except to say that reviews seem to be overwhelmingly positive. People who know far more than I do about gaming argue that this is the future of video games. I have no reason to doubt that.

Apple, however, isn’t having it.

According to Microsoft:

“Our testing period for the Project xCloud preview app for iOS has expired. Unfortunately, we do not have a path to bring our vision of cloud gaming with Xbox Game Pass Ultimate to gamers on iOS via the Apple App Store. Apple stands alone as the only general purpose platform to deny consumers from cloud gaming and game subscription services like Xbox Game Pass.”

You might argue that the reason Apple rejected xCloud, along with Google Stadia and Facebook Games before it, is that it already offers a competing gaming service, Apple Arcade. Maybe, but I doubt it.

According to Apple, the main reason it won’t allow streaming game services is that it isn’t able to review every app individually. In a statement, Apple said:

“The App Store was created to be a safe and trusted place for customers to discover and download apps, and a great business opportunity for all developers. Before they go on our store, all apps are reviewed against the same set of guidelines that are intended to protect customers and provide a fair and level playing field to developers.

Our customers enjoy great apps and games from millions of developers, and gaming services can absolutely launch on the App Store as long as they follow the same set of guidelines applicable to all developers, including submitting games individually for review, and appearing in charts and search. In addition to the App Store, developers can choose to reach all iPhone and iPad users over the web through Safari and other browsers on the App Store.”

As I’ve thought about it, while the two arguments look different (Epic and Microsoft), there is actually a common thread, which is the ability to remove the middleman. Microsoft isn’t specifically asking for its own “store,” but rather wants to be able to simply stream games from another source, within a single app in a way many have compared to Netflix. I happen to think that’s the wrong analogy, and I’ll explain why in a minute.

Microsoft is wrong because it wants to define the boundaries of Apple’s platform differently than it has defined its own. Did you happen to notice the interesting little carve out Microsoft makes for itself when it explains why Xbox Game Pass Ultimate (because Microsoft is really second only to Google when it comes to product names), isn’t available on the iPhone.

“Apple stands alone as the only general purpose platform to deny consumers from cloud gaming”

Microsoft wants to argue over the idea that the iPhone is a “general purpose platform,” and therefore is subject to some specific set of rules that should govern how Apple makes that platform available to developers.

There are two problems. Inherent in Microsoft’s argument is the acknowledgement that there are some types of computing devices for which the available content and services can be tightly controlled. The Xbox is one of those “console” devices. Microsoft wants to make it clear that it doesn’t think the iPhone is one.

Here, Microsoft is wrong.

Why Netflix Is the Wrong Analogy

A brief aside about Netflix. I’ve listened to, and read, many reasonable arguments that compare streaming games, for example, to Netflix. I said before that I don’t think this is the right analogy.

Okay, fine, a video game is simply video streamed down and interactive commands streamed back. Technically that’s the same as what happens in Netflix, except, it isn’t.

No matter how many times you press pause and then play, the episode of Stranger Things doesn’t change change. It’s linear video and its frames all occurs in the same order. Yes, you can skip around and watch those frames in any order you want, but first, that’s nonsense, and second, you still didn’t change the story, you just messed it up.

That isn’t what happens with video games. The interactions you have with a video game determine the story. It’s actually interactive.

It’s also different because of the user experience and expectation. Videos on Netflix also don’t have the ability to interact with other aspects of your device in the way an app potentially can. Apple isn’t worried that a Netflix original is going to suddenly drop its own payment method in order to fast-forward the film past the credits, for example. The same can’t be said for games, and Apple isn’t giving up control over that part of the experience, at least not when it comes to video games.

A Third Type of Thing

I tend to agree with John Gruber that the iPhone is a console, if for no other reason than Apple considers it such. It’s just happens to be the most versatile console ever made, with far greater scope and scale than one that simply plays games.

Of course, there are like 65 million Xbox users, compared to the 1.5 billion people with iOS devices. The stakes are of no comparable scale.

Though I think that might also mean that it isn’t. As I think about it, the argument between “console” and “general purpose platform” isn’t the right one because I don’t think that a smartphone is necessarily either, but is—at the same time—both. It’s a third type of thing.

A smartphone is part general purpose computer in that it does a wide range of things, and part console in that the user experience is tightly controlled.

You could even argue that the iPhone was clearly designed originally to be fully in the console category. Third-party apps weren’t even a thing at first, aside from Google Maps, but there wasn’t an App Store to download them.

Even after Apple added the ability to download other apps, the reason it exerted so much control was largely because it felt the need to protect the user experience in order to be sure the thing was good. And by “thing” I don’t mean apps, I mean the iPhone. Apple’s control over the App Store is, at its core, meant to make the iPhone the best possible user experience.

That doesn’t mean Apple doesn’t also benefit from that control, it absolutely does. The App Store is ridiculously profitable for Apple, and drives most of the growth in its crucial services division.

But, I’m not entirely sure it’s fair to say that profit is the primary driver behind the control. Sure, you might think I’m naive, that’s fine. Except, that control of the user experience is exactly what has made the iPhone so popular. That refined user experience is why an iPhone is far easier to use than a computer. It’s why my grandmother could use her iPhone long after she could no longer figure out how to check her email on her Windows PC.

Control isn’t necessarily a bad thing unless it leads to an unfair monopoly.

Defining the Market

By the way, not all monopolies are inherently unfair or anticompetitive. Obviously, if Apple has a monopoly over a market, it depends on how you define that market. Epic wants to define that market as “the distribution of software applications (“apps”) to users of mobile computing devices like smartphones and tablets, and (ii) the processing of consumers’ payments for digital content used within iOS mobile apps (“in-app content”).”

Basically, Epic is accusing Apple of having a monopoly over the iPhone, which, I mean, of course it does. Apple makes the iPhone. That reality is neither complicated or controversial.

This, by the way, explains Tim Cook’s statement when he testified before the Antitrust Subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee. In it he made it clear that Apple views the App Store as a “feature” of the iPhone.

If that’s true, then of course Apple has a monopoly, just like it has a monopoly on the camera. No one can sell cameras that you can swap in for the one that Apple built in when it was assembled. It’s a feature of the device. Also, no one is complaining about it. No one accuses Apple of being monopolistic because you are limited to the functionality of the camera that it chooses or that it’s unreasonably restrictive that you can’t add one from someone else.

Of course, where that argument breaks down is because in many cases Apple not only offers the market, but also offers products within that market, putting competitors at a disadvantage. Spotify would have to pay Apple 30 percent in order to sign up customers via in-app purchases. Apple Music, on the other hand, doesn’t have to pay that same tax.

Except, we don’t make that argument when it comes to iPhone cases sold at the Apple Store. Apple makes iPhone cases. So do a lot of other companies. Many of those other companies sell their cases in Apple’s retail stores. When they do, Apple gets a cut. That’s not controversial at all. Does Apple have a monopoly on the market of “things sold in the Apple Store?” Of course it does, it’s Apple’s store.

The question isn’t whether Apple can exert this level of control, but rather whether it should. Those are very different questions, and it really gets to the core of the problem.

Apple Is Right, Sort Of

Apple’s Developer Program License Agreement is pretty clear on the consequences for doing what Epic did. Section 11.2 says:

This Agreement and all rights and licenses granted by Apple hereunder and any services provided hereunder will terminate, effective immediately upon notice from Apple:

(f) if You engage, or encourage others to engage, in any misleading, fraudulent, improper, unlawful or dishonest act relating to this Agreement, including, but not limited to, misrepresenting the nature of Your submitted Application (e.g., hiding or trying to hide functionality from Apple’s review, falsifying consumer reviews for Your Application, engaging in payment fraud, etc.).

There’s really no way around it, Epic clearly violated the terms, and did so intentionally. In fact, it didn’t just do so for the purpose of skirting the rules, it did it just to pick a fight. I don’t think there’s any way to argue that Apple isn’t acting within its right to terminate Epic’s membership in the Apple Developer Program (ADP).

You could even argue that Apple is acting with a measure of restraint. According to those terms, Apple could have terminated Epic “immediately upon notice.” Instead, Apple gave Epic a way out.

Apple’s statement:

The App Store is designed to be a safe and trusted place for users and a great business opportunity for all developers. Epic has been one of the most successful developers on the App Store, growing into a multibillion dollar business that reaches millions of iOS customers around the world. We very much want to keep the company as part of the Apple Developer Program and their apps on the Store.

The problem Epic has created for itself is one that can easily be remedied if they submit an update of their app that reverts it to comply with the guidelines they agreed to and which apply to all developers. We won’t make an exception for Epic because we don’t think it’s right to put their business interests ahead of the guidelines that protect our customers.

It’s true, Epic’s problem is of its own making, and any collateral damage that might occur to third-parties as a result of its action is Epic’s fault. That includes Unreal Engine, which Epic points out would be unavailable to developers who want to make games for iOS if the company is no longer allowed access to the tools that make that possible.

Apple is also right when it comes to streaming games. Well, it’s right in the sense that they aren’t allowed under the current “rules.” Should those rules change? Possibly.

Many of the arguments that I’ve heard for why Apple is wrong are basically just that people don’t like the way Apple is managing the App Store. Meaning, Apple is acting in a manner counter to their personal preference. If you want Stadia or xCloud to be available on the iPhone, you think Apple is wrong. If you think you should be able to set up a Hey email account in the app, without Apple taking a cut of the subscription, you probably think Apple’s position is wrong.

Take Facebook for example. It seems as though every business that thinks its service is super valuable to consumers deserves an exception from the App Store’s rules. “hey, people should be able to use Facebook gaming. Apple is wrong.”

Apple is trying to prevent a scenario where a company like Microsoft, instead of submitting apps to Apple for review, and making them available in the App Store, simply submits its own catalog app.

Microsoft absolutely could submit each app individually and would probably make more money selling them to iPhone users. Microsoft is making a business decision, but wants us to think that it simply doesn’t care for the way Apple is gating access to the iPhone. Except, Microsoft does the same thing with the Xbox.

By the way, there’s a reason Apple isn’t interested in Epic, or anyone else running its own App Store, or allowing streaming gaming services like xCloud, ahem, Xbox Game Pass Ultimate.

Arguably the main thing Apple cares about is avoiding a scenario where other tech companies, full of very smart developers and shrewd executives, figure out ways to bypass Apple’s control over the user experience on iOS devices.

Every time you create a “rule” that allows for an exception of a certain type of business or app, you open the door to a myriad of unforeseen circumstances.

Apple simply isn’t going to go down that road until it figures out whether it can do so in a way that still allows it to maintain a level of control over the experience (and probably still get a cut).

I don’t think the problem is streaming gaming services. I think the problem is the line. Until now, the line has been somewhat clear—you develop an app and submit it to Apple.

Microsoft and Epic want Apple to move the line.

Where Apple Is Definitely Wrong

I spent a lot of time making the case for why I think Apple is right, but ultimately, I’m not sure that matters. In fact, I believe that being right is probably wrong for Apple and definitely wrong for users.

The problem for Apple, and this isn’t a small issue, is that all of this is creating a worse experience for users, which is something that has long been anathema to Apple. Honestly, that’s the only reason this is an issue—the customer experience is worse because of the standoff between Apple and all of these developers.

That isn’t to say that I don’t think that the damage the company is doing to its relationship with developers isn’t consequential on its own. It definitely is, and developer relations are—and should be—a very real concern. I even heard John Siracusa on the Accidental Tech Podcast argue that, compared to Microsoft and Sony, Apple has done a terrible job with developer relations. That’s absolutely true.

I do think that part matters, but it’s honestly secondary to the user experience issue. Apple and developers should be able to work out their differences on their own, not in a way that creates a bad experience for the people who give them money.

Also, there’s the fact that Apple is inviting even more scrutiny from regulators on both sides of the Atlantic which already seem intent on finding a way to force it to change. If Apple thinks avoiding that is important, this isn’t helping. We’ll get back to this in a moment.

I also think there’s an argument to be made that Apple is wrong because it come to a point where the policies it uses to govern the App Store have betrayed the values it was founded on. Primarily that’s the user experience. People want to be able to play games on their iPhone. I mean, I don’t, but a lot of people do. Making it harder for those people to use their device the way they want is wrong.

Apple is also wrong because the level of control it exerts isn’t actually making it better. Apple isn’t getting better, and neither are its services.

Take the rumor that Apple is planning to introduce a streaming fitness service. Apple absolutely could start its own fitness video streaming service, but it probably shouldn’t. It probably won’t be better than what’s already available.

AppleTV+ isn’t better than Netflix or Disney+. Apple Arcade is nice, but it isn’t better than xCloud. iCloud is a really useful way to sync pretty much everything across devices, but it isn’t better than Dropbox at file management or collaboration.

Every product or service is better when there’s competition, and to the extent that Apple can simply strong-arm anyone else who tries to compete in those spaces means the services won’t be better. That’s wrong.

There’s Something Worse Than a Monopoly

By the way, if Apple really does have a monopoly on the market that is App Stores on the iPhone, then it should figure out the best remedy by working with developers now. If it doesn’t, regulators, Congress, and the courts absolutely will act. It’s only a matter of time at this point.

That should worry everyone because there is something worse than a monopoly. It’s called Congress.

Can you imagine if Congress decided that there were specific types of computing devices and then wrote rules governing each? I promise you that if you think it’s bad that Apple gets to decide what you can put on your iPhone, it’ll be far worse if it’s up to the government.

Apple may think it can win a court case against Epic under the terms of its agreement, and the laws that exist today. The problem is that it very well may be inviting a change to those laws as a result. Apple is a big enough company, and it’s full of enough smart people, that it will certainly find a way to adapt.

But there is absolutely no question that if Congress passes laws to further regulate the tech industry, the situation for everyone will be worse. It would be far better for Apple to simply find a better way, one that makes everyone as happy as possible without inviting further scrutiny or regulation.

The Apple Thing to Do

That isn’t impossible. Apple’s overarching principle here should be to do what’s right for its users, which—by the way—leads to a better experience, which leads to brand loyalty, which leads to more profit.

That is literally how Apple became the largest, most profitable, and most valuable company in the world. Steve Jobs was an extraordinarily smart business person who knew that the way to give people exactly what they needed and wanted, when they had no clue what they needed or wanted. That obsessive focus on the user is what made people love Apple in the first place, and powered its growth to become the first $2 trillion company.

But, right now, it feels to many observers—including many long-time loyal Apple users—that the company has lost sign of that focus on the user. What’s even more complicated is that it seems that Apple thinks it’s doing the right thing for the user, but can’t see that it’s actually making the experience worse.

Of course, there’s an argument that what Apple is doing now is absolutely the Apple thing to do, and that’s not a good thing. Meaning that what Apple has become is a very different company than the one that cared about the user experience. Apple very well may believe that its platform is more important than any individual app or developer.

That wasn’t always true. There was a time that Adobe and Microsoft’s software products were far more important to users than the Mac. If the Mac didn’t support Photoshop or Word, forget about it, the Mac would have no longer been a thing. That’s just reality.

Today, Apple clearly thinks its platform is more important to users than Fortnite or Microsoft or Netflix. If that’s true, it means it also believes its platform is more important than its users, which is bad.

Apple has to figure out the Apple thing to do, the thing that re-centers the conversation on the user. I happen to believe, if it does, it will also benefit both Apple and developers.

Here’s how:

It would seem that the easiest change would be to allow apps to tell users that they can’t sign up in the app, but can by visiting the service directly. Meaning, in the case of a company like Hey or Netflix, they could simply tell you how to sign up. It’s literally absurd that developers can’t do this.

But I think Apple should go further. I think that the best experience for the user would be to give developers a choice to direct customers to their service if they also include in-app purchases. Imagine if, when you downloaded the Netflix app and opened it for the first time, you were given two options: Create an Account with Apple and Create an Account with Netflix.

Button one uses the in-app purchase. Button two takes you to a web view of Netflix’s site. Apple wouldn’t get anything when people click on that button, but iPhone users would get a better experience because it’s available. And, if given this option, companies very well might go for it. They could even charge a little more for the Apple IAP version. Let the customers decide whether they value the security and certainty of Apple, or go through the developer directly.

In the case of Netflix, most people will probably go to the site to sign up, which is fine—Apple isn’t getting anything from Netflix right now anyway. Netflix is a large enough, and trusted enough company on its own that people will do that.

But imagine if Apple made that option to other developers. You can add a button to direct people to your site to sign up, but you also have to allow in-app subscriptions or purchases.

There are plenty of services people would never give their information to directly, but would only sign up through the in-app purchase because it’s managed by Apple. Developers can make that call. If you choose not to use in-app purchase, you risk losing customers.

I suspect there is a correlation between the apps that are able to stand on their own (without the benefit of in-app subscriptions) and those that Apple would prefer to keep on their platform even if they aren’t going to get a cut. Their presence alone adds value to the overall iOS experience, which means it adds value to Apple.

That’s subscriptions.

If a business is selling real-world goods, then it doesn’t pay Apple anything. That’s already the case. When you place an order at Starbucks, you use Starbucks’ payment processing system and it keeps all the money. Apple gets nothing. Otherwise, there’s no scenario where you’d ever be able to order a Carmel Frappucino from Starbucks on your iPhone—at least not in an app.

Then, Apple could, as a good-faith move, change its pricing structure to a tiered system as follows:

Subscription services pay 20 percent the first year, 10 percent the second year.

In-app purchases for games are 25 percent.

All other app developers that offer paid app (non-subscription) are a flat 20 percent.

(If you think those numbers are wrong, okay, tell me what’s better.)

Apple would more than make up for the loss on a percentage basis simply because some developers would likely come back. There are very real benefits to the simplicity of Apple’s payment system including the fact that people trust it and are more likely to sign up or buy when it’s an option.

There’s also the fact that it incentivizes Apple to help developers acquire new customers. The best business partnership is when both sides gets something they want (even if not everything).

Apple could even waive, or reduce the commission in exchange for a “marketing partnership.” For example, take a company like Netflix. There’s a world where Netflix might consider adding in-app-purchases through Apple if it could negotiate some kind of favorable agreement.

There’s a part of me that hesitates to even make that suggestion since it seems very “un-Apple-like,” except this is essentially what it did with Amazon Prime Video, for which Apple doesn’t collect a commission when rent or purchase content within the app.

You might argue that would go against Apple’s position that it treats all developers the same, but businesses enter into deals and arrangements all the time that account for the total amount of revenue involved. Call it a volume discount.

My point is, there’s another way for Apple to do The Apple Thing, without putting its business at risk. When it comes to Apple and developers, sometimes a little good faith can move what otherwise seem like immovable objects. Right now, its unwillingness to do that is putting the user experience at risk, which for many is just as bad.